New Name Reflects Neuroscience Growth at UT

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy

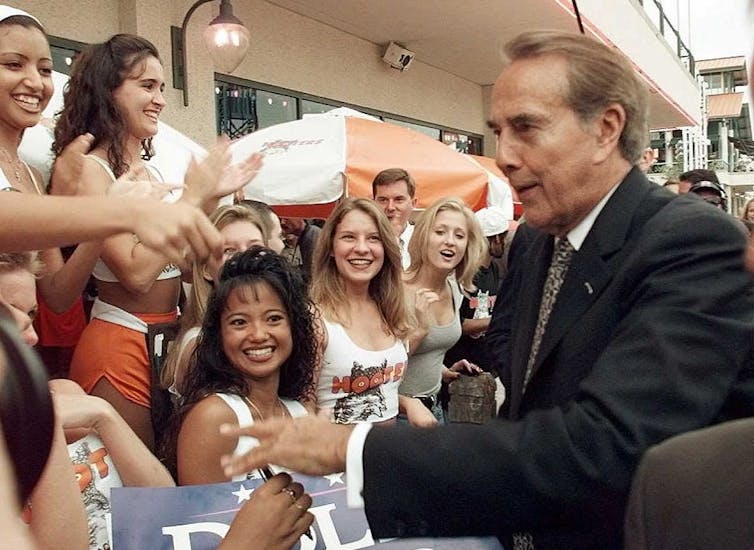

In 1983, six businessmen got together and opened the first Hooters restaurant in Clearwater, Florida. Hooters of America LLC quickly became a restaurant chain success story.

With its scantily clad servers and signature breaded wings, the chain sells sex appeal in addition to food – or as one of the company’s mottos puts it: “You can sell the sizzle, but you have to deliver the steak.” It inspired a niche restaurant genre called “breastaurants,” with eateries such as the Tilted Kilt Pub & Eatery and Twin Peaks replicating Hooters’ busty business model.

A decade ago, business was booming for breastaurant chains, with these companies experiencing record sales growth.

Today it’s a different story. Declining sales, rising costs and a large debt burden of approximately US$300 million have threatened Hooters’ long-term outlook. In summer 2024, the chain closed over 40 of its restaurants across the U.S. In February 2025, Bloomberg reported that the company was on the verge of filing for bankruptcy.

Hooters isn’t necessarily going away for good. But it’s certainly looking like there will be fewer opportunities for women to work as “Hooters Girls” – and for customers to ogle at them.

As a psychologist, I was originally interested in studying servers at breastaurants because I could sense an interesting dynamic at play. On the one hand, it can feel good to be complimented for your looks. On the other hand, I also wondered whether constantly being critiqued might eventually wear these servers down.

So my research team and I decided to study what it was like to work in places like Hooters.

In a series of studies, here’s what we found.

More so than most restaurants, managers at breastaurants like Hooters seek to strictly regulate how their employees look and act.

For one of our studies, we interviewed 11 women who worked in breastaurants.

Several of them said that they were told to be “camera ready” at all times.

One described being given a booklet with exacting standards outlining her expected appearance, down to “nails, hair, makeup, brushing your teeth, wearing deodorant.” She had to promise to stay the same weight and height, wear makeup every shift and not change her hairstyle.

Beyond a carefully constructed physical appearance, the servers relayed that they were also expected to be confident, cheerful, charming, outgoing and emotionally steeled. They were instructed to make male customers feel special, to be their “personal cheerleaders,” as one interviewee put it, and to never challenge them.

Suffice it say, these demands can be unrealistic – and many of the servers we interviewed described becoming emotionally drained and eventually souring on the role.

It probably won’t come as a surprise that Hooters servers often encounter lewd remarks, sexual advances and other forms of sexual harassment from customers.

But because their managers often tolerate this behavior from customers, it created the added burden of what psychologists call “double-binds” – situations where contradictory messages make it impossible to respond properly.

For example, say a regular customer who’s a generous tipper decides to proposition a server. Now she’s in a predicament. She’s been instructed to make customers feel special. And he’s already left a big tip, in addition to being a regular. But she also feels creeped out, and his advances make her feel worthless. Should she push back?

You might assume that managers, aware that their scantily clad employees would be more likely to face harassment, would try to set boundaries and throw out customers who treated servers poorly. But we found that waitresses at breastaurants have less support from both management and their co-workers than servers at other restaurants.

“Unfortunately, the girls are a dime a dozen, and that’s how they’re treated,” a former server and corporate trainer at a breastaurant explained.

The lack of co-worker support might also come as a surprise. Rather than standing in solidarity, the servers tended to compete for favoritism, better shifts and raises from their bosses. Gossiping, name-calling and scapegoating were commonplace.

My research team also wanted to learn more about the specific emotional and psychological costs of working in these types of environments.

Psychologists Barbara Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Robert have found that mental health problems that disproportionately affect women often coincide with sexual objectification.

So we weren’t surprised to find that servers working in sexually objectifying restaurant environments, such as Hooters and Twin Peaks, reported more symptoms of depression, anxiety and disordered eating than those working in other restaurants. In addition, they wanted to be thinner, were more likely to monitor their weight and appearance, and were more dissatisfied with their bodies. Hooters didn’t reply to a request for comment on this story.

Given our findings, you might wonder why any women would choose to work in places like Hooters in the first place.

The women we interviewed said that they sought work in breastaurants to make more money and have more flexibility.

A number of servers in one of our studies noted that they could make more money this way than waitressing at a regular restaurant or in other “real” jobs.

For example, one of the servers we interviewed used to work at a more run-of-the-mill restaurant.

“It was OK, I made OK money,” she told us. “But working at Hooters … I’ve walked out with hundreds of dollars in one shift.”

All the women we interviewed were in college or were mothers. So they enjoyed the high degree of flexibility in their work schedule that breastaurants provided.

Finally, several of them had previously experienced objectification while growing up, or they’d participated in activities centered on physical appearance, such as beauty pageants and cheerleading. This likely contributed to their decision to work at a Hooters or one of its competitors: They’d been objectified as adolescents, and so they found themselves drawn to these kinds of setting as adults.

Even so, our research suggests that the financial rewards and flexibility of working in breastaurants probably aren’t worth the potential psychological costs.![]()

Dawn Szymanski, Professor of Psychology, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

by Logan Judy

Cass Bennett has been with the Psychology Advising Center since October 2022. They have been working as a professional counselor since 2012 and started their own practice specializing in ADHD, religious trauma, and LGBTQ+ folks in 2018. Taking on their role as an advisor has allowed them to step away from their practice part-time, which has been a welcome change. In their free time they enjoy cooking, backpacking, rock climbing, and hiking with their wife, Meghan.

Kristi Cook has dedicated 12 years to the University of Tennessee, where she has expertly managed travel expense reports and maintained detailed ledgers. Her extensive experience in financial handling has made her an invaluable resource within the institution. Now in her senior year, Cook is pursuing her undergraduate degree in political science, combining her financial acumen with a deep understanding of political systems. Her commitment to excellence and her ability to balance academic and professional responsibilities highlight her dedication and skill. Cook is a financial associate and her comprehensive background positions her well for future challenges in both finance and political fields.

Susan Hawthorne grew up in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, studied media in college, and then moved to Knoxville, where she has lived ever since. Her first job out of college was as a fact checker/researcher at Whittle Communications. Hawthorne then worked at Scripps Networks Interactive doing background research for television series, finding stories to feature, and producing online videos. Research meant talking with people across the country about their lives, which was one of her favorite things about this work. Currently she is an administrative assistant in the department, where she hires new employees, keeps up our accreditations, and helps with office needs.

Jackson Knight was born in Knoxville but has only just returned home within the last few years. In that time, he has worked around UT in various departments and experienced a multitude of what the university offers and how it functions. He is currently taking classes in media technology and learning what it is like to work in a post-production environment for different forms of media. He is excited to be helping out the department as an administrator and undergraduate assistant, hoping to make life easier for all.

Sharon Sparks has been with UT for 15 years, and most of those years were spent at the agriculture campus in the School of Natural Resources (formerly the Department of Forestry, Wildlife, and Fisheries) as the financial associate. She joined the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience in 2023 and is a financial associate with responsibilities for accounts payable, processing travel reimbursements, and other financial duties.

Cidae’a Woods has been working as an academic advisor in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience since fall 2022. She earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology in 2018 and a master’s degree in kinesiology with a concentration in sport psychology and motor behavior in May 2022, both from UT. Woods is originally from New Jersey and came to UT as an undergraduate student-athlete for women’s track and field. She is currently enrolled at UT in the Master of Social Work program with a clinical concentration, and she has an interest in working in a clinical setting as a therapist in the future.

by Logan Judy

Jasmine Coleman earned her PhD in clinical psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University. Her broad research goal is to advance our understanding of ways to reduce mental and behavioral health disparities experienced by Black youth. She aims to achieve this by identifying and addressing the unique and interactive roles of Black youths’ community, peer, and family microsystems in the development of mental health and behavioral problems. Her current work focuses on examining how youths’ justice involvement may impact their family members, particularly siblings’ justice involvement and youths’ adjustment in sibling dyads.

Sarah Diorio completed her doctoral degree in clinical psychology at Immaculata University in Pennsylvania and completed her internship and postdoctoral residency at Mid-Atlantic Behavioral Health in Delaware. She is in her eighth year of teaching, previously teaching in both undergraduate and graduate psychology programs at Rowan University in New Jersey. Diorio joined our department in 2023 primarily teaching General Psychology, Theories of Personality, and Abnormal Psychology. When not teaching she is a clinician working in therapeutic and assessment services, with a specialty in general mental health and psychological diagnosis and evaluation.

Claire Hemingway’s lab broadly explores the mechanisms, outcomes, and evolutionary consequences of animal decision-making. To address these questions, they study foraging behavior in both bats and bees to test how animals evaluate and make decisions between foraging options based on the signal and reward properties of each option. They also ask whether species differ in decision-making mechanisms based on their foraging strategy or other aspects of their ecology. Finally, they are interested in how certain decision mechanisms may shape the targets of those decisions, such as floral signals and rewards.

Justina Hyfantis earned her PhD in counseling psychology from UT and completed her internship at the UT Student Counseling Center. She completed postdoctoral training at the Counseling and Psychological Services Center at Appalachian State University and returned to UT in fall 2024 as a clinical assistant professor. Her clinical experience includes specialization in individual and group therapy for young adults, career counseling, and academic success. Hyfantis’ approach to both clinical practice and supervision is integrative and primarily influenced by interpersonal process, cognitive-behavioral, and humanistic theories, couched within a strengths-based lens.

Trenton Johanis joined the department in 2024 as a lecturer and has a PhD from the University of Toronto. As a researcher, his primary interests are in music psychology, studying experiences and effects of flow states in piano performances, as well as other topics. He also has completed research projects in developmental and social psychology.

Lucybel Mendez is an assistant professor in the clinical program. She received her clinical psychology PhD from the University of Utah and completed her predoctoral internship at the University of Illinois-Chicago. Mendez’s research focuses on: 1) trauma-informed developmental trajectories to mental health and behavioral problems among marginalized and minoritized youth; 2) socioecological risk and protective factors underlying these pathways; 3) trauma-focused prevention and intervention outcomes; 4) trauma-informed care in youth-serving systems; and 5) policy and advocacy efforts that promote access to mental health services and wellbeing for youth and their families.

Ryan Mokhtari earned his PhD in neuroscience from SUNY Upstate Medical University, studying molecular genetics of autism spectrum disorder, using induced pluripotent stem cells. He had previously received his MD in Iran and worked in the field of psychiatry for a few years in Australia. Mokhtari also received a research fellowship from Einstein College of Medicine in New York, where he worked on epigenetic mechanisms of neurodevelopmental disorders. Mokhtari teaches undergraduate courses on behavioral neuroscience, behavioral genetics, neuroscience journal club, and evolutionary psychology. He is a member of the UT Undergraduate Council.

Cynthia M. Navarro Flores is a bicultural/bilingual Mexican psychologist and assistant professor in the counseling psychology program. She co-directs the THRIVE Lab (Targeting Health Disparities through Research, InnoVation, and Equity). She earned her PhD in combined clinical/counseling psychology at Utah State University and completed her pre-doctoral internship in the child emphasis track at the Medical University of South Carolina. Her research aims to reduce mental health disparities in marginalized youth and families, particularly within Latinx/e communities, by understanding mechanisms of resilience and adversity and increasing access to culturally competent evidence-based interventions.

Alejandro L. Vázquez is a bicultural/bilingual Cuban American psychologist and assistant professor of counseling psychology at UT. He earned his PhD in combined clinical/counseling psychology at Utah State University and completed his pre-doctoral clinical internship at the Medical University of South Carolina (child emphasis track). His research focuses on reducing mental health disparities in underserved populations with a specific interest in Latinx youths and families. Within this broad scope, he is interested in identifying needs, mechanisms influencing caregiver help-seeking, and improving the delivery and accessibility of evidence-based interventions.

Alejandro Vélez Melendez is originally from Bogotá, Colombia, where he obtained a BS and an MS in biology from Universidad de Los Andes. He completed his PhD at the University of Minnesota and postdoctoral work at Purdue University and Washington University in St. Louis. After some years as a faculty member at San Francisco State University, he joined the UT’s Department of Psychology and Neuroscience in 2023. His research program seeks to understand patterns of brain evolution and how they relate to diversification of perception and behavior. His lab integrates ecological, behavioral, physiological, and anatomical studies, under a comparative framework, to investigate the mechanisms, function, and evolution of animal communication signals and signal-processing mechanisms.

Caitlin Williams is a native North Carolinian, born and raised in the Asheville area, who earned her PhD in clinical psychology from George Mason University in 2020. She completed her required clinical internship on the child track at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Her first postdoctoral fellowship was at Cherokee Health Systems in Knoxville, and her second was at the Center of Excellence for Children in State Custody through the UT Graduate School of Medicine. She specializes in trauma-focused and informed interventions, including Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, in which she is a within-agency trainer. Her assessment experience includes child and adult assessment for psychoeducational, psychodiagnostic, and trauma-focused assessments.

by Logan Judy

Greetings alumni and friends,

I want to share some exciting updates from the fall semester as we begin the new year.

Our undergraduate degree programs in psychology and neuroscience and our graduate programs continue to thrive. Given our large numbers of undergraduate majors and graduate students, we were given the exciting opportunity to search for two new tenure-track assistant professors who will join us in August.

Earlier this academic year, the department decided to add a new health services psychology concentration to the psychology major. We’re excited about this option for our undergraduate students who are focused on a range of health service careers in mental health and medicine. Also, as you may be aware, the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, is increasing its digital learning offerings, and our department has voted to move forward with offering an online BA in psychology. The online degree program will begin in fall 2026.

Several members of our department are serving as leaders in new collaborative, interdisciplinary units for College of Arts and Sciences faculty, students, and partners across the university. Professor Todd Freeberg is associate director of the Collaborative for Animal Behavior (CoLAB) research center, and leadership of the Consortium for the Study of Black Families and Children includes Associate Professor Jennifer Bolden and Assistant Professor Jasmine Coleman. Professor Erin Hardin is representing social sciences in the new Community of Scholars for Advancing Teaching Excellence (CATE).

In other exciting news, we held our first Psychology Alumni Tailgate prior to the UT football game on homecoming weekend in 2024. It was great seeing those of you who could make it to the event! We hope to host the tailgate in the future, so please stay tuned.

We had several important faculty transitions in the department last year (see updates on pages 4-5). Associate Professor Debora Baldwin retired in December 2024 after 35 years as a member of the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience. Baldwin was part of our neuroscience and behavior program area and will be missed. We wish her well in her retirement!

In addition to updates with our faculty, we also want to welcome two new administrative staff to our department. Kristi Cook joined the department in July as a financial associate, having had over a decade of experience in finance at UT. Jackson Knight joined us in August as an administrative specialist assisting with our undergraduate programs. We are thrilled to have them in our department!

Finally, I want to sincerely thank you for your generous support of the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience! Between Fall 2022 and Spring 2024, your donations provided:

It is our pleasure to share these exciting developments with you as we embark on a new year and new semester. We hope you are healthy and well. Please stay in touch. Go Vols!

Gina Owens

Professor and Head

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy