New Name Reflects Neuroscience Growth at UT

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy

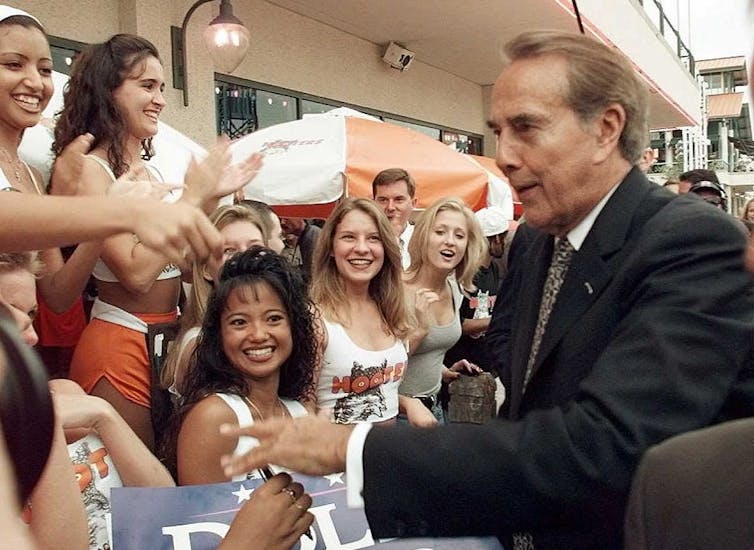

In 1983, six businessmen got together and opened the first Hooters restaurant in Clearwater, Florida. Hooters of America LLC quickly became a restaurant chain success story.

With its scantily clad servers and signature breaded wings, the chain sells sex appeal in addition to food – or as one of the company’s mottos puts it: “You can sell the sizzle, but you have to deliver the steak.” It inspired a niche restaurant genre called “breastaurants,” with eateries such as the Tilted Kilt Pub & Eatery and Twin Peaks replicating Hooters’ busty business model.

A decade ago, business was booming for breastaurant chains, with these companies experiencing record sales growth.

Today it’s a different story. Declining sales, rising costs and a large debt burden of approximately US$300 million have threatened Hooters’ long-term outlook. In summer 2024, the chain closed over 40 of its restaurants across the U.S. In February 2025, Bloomberg reported that the company was on the verge of filing for bankruptcy.

Hooters isn’t necessarily going away for good. But it’s certainly looking like there will be fewer opportunities for women to work as “Hooters Girls” – and for customers to ogle at them.

As a psychologist, I was originally interested in studying servers at breastaurants because I could sense an interesting dynamic at play. On the one hand, it can feel good to be complimented for your looks. On the other hand, I also wondered whether constantly being critiqued might eventually wear these servers down.

So my research team and I decided to study what it was like to work in places like Hooters.

In a series of studies, here’s what we found.

More so than most restaurants, managers at breastaurants like Hooters seek to strictly regulate how their employees look and act.

For one of our studies, we interviewed 11 women who worked in breastaurants.

Several of them said that they were told to be “camera ready” at all times.

One described being given a booklet with exacting standards outlining her expected appearance, down to “nails, hair, makeup, brushing your teeth, wearing deodorant.” She had to promise to stay the same weight and height, wear makeup every shift and not change her hairstyle.

Beyond a carefully constructed physical appearance, the servers relayed that they were also expected to be confident, cheerful, charming, outgoing and emotionally steeled. They were instructed to make male customers feel special, to be their “personal cheerleaders,” as one interviewee put it, and to never challenge them.

Suffice it say, these demands can be unrealistic – and many of the servers we interviewed described becoming emotionally drained and eventually souring on the role.

It probably won’t come as a surprise that Hooters servers often encounter lewd remarks, sexual advances and other forms of sexual harassment from customers.

But because their managers often tolerate this behavior from customers, it created the added burden of what psychologists call “double-binds” – situations where contradictory messages make it impossible to respond properly.

For example, say a regular customer who’s a generous tipper decides to proposition a server. Now she’s in a predicament. She’s been instructed to make customers feel special. And he’s already left a big tip, in addition to being a regular. But she also feels creeped out, and his advances make her feel worthless. Should she push back?

You might assume that managers, aware that their scantily clad employees would be more likely to face harassment, would try to set boundaries and throw out customers who treated servers poorly. But we found that waitresses at breastaurants have less support from both management and their co-workers than servers at other restaurants.

“Unfortunately, the girls are a dime a dozen, and that’s how they’re treated,” a former server and corporate trainer at a breastaurant explained.

The lack of co-worker support might also come as a surprise. Rather than standing in solidarity, the servers tended to compete for favoritism, better shifts and raises from their bosses. Gossiping, name-calling and scapegoating were commonplace.

My research team also wanted to learn more about the specific emotional and psychological costs of working in these types of environments.

Psychologists Barbara Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Robert have found that mental health problems that disproportionately affect women often coincide with sexual objectification.

So we weren’t surprised to find that servers working in sexually objectifying restaurant environments, such as Hooters and Twin Peaks, reported more symptoms of depression, anxiety and disordered eating than those working in other restaurants. In addition, they wanted to be thinner, were more likely to monitor their weight and appearance, and were more dissatisfied with their bodies. Hooters didn’t reply to a request for comment on this story.

Given our findings, you might wonder why any women would choose to work in places like Hooters in the first place.

The women we interviewed said that they sought work in breastaurants to make more money and have more flexibility.

A number of servers in one of our studies noted that they could make more money this way than waitressing at a regular restaurant or in other “real” jobs.

For example, one of the servers we interviewed used to work at a more run-of-the-mill restaurant.

“It was OK, I made OK money,” she told us. “But working at Hooters … I’ve walked out with hundreds of dollars in one shift.”

All the women we interviewed were in college or were mothers. So they enjoyed the high degree of flexibility in their work schedule that breastaurants provided.

Finally, several of them had previously experienced objectification while growing up, or they’d participated in activities centered on physical appearance, such as beauty pageants and cheerleading. This likely contributed to their decision to work at a Hooters or one of its competitors: They’d been objectified as adolescents, and so they found themselves drawn to these kinds of setting as adults.

Even so, our research suggests that the financial rewards and flexibility of working in breastaurants probably aren’t worth the potential psychological costs.![]()

Dawn Szymanski, Professor of Psychology, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy

When Sandy Thomas was looking for a job in 1986, a good friend encouraged her to apply at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Because of the people in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, she stayed for 38 years.

Thomas started as a “suite secretary,” sharing responsibilities with another staff member and working with about half a dozen professors. After a while she started working for the director of undergraduate studies, and her responsibilities evolved to include scheduling and registration. She was an administrative specialist before her retirement in August, also serving as a departmental liaison for students and planning the annual awards night.

“Working with students is one of the main reasons I stayed at UT,” Thomas said.

They appreciated her too, with several naming her in the acknowledgements of their doctoral dissertations. Before the work moved to personal computers, Thomas explained, she typed many graduate students’ dissertations.

Thomas also represented the College of Arts and Sciences for numerous years on the Employee Relations Committee (ERC). “I feel that the ERC is a very important outlet for staff to voice their concerns as well as share ideas to help make changes to benefit all staff,” she said.

“UT is a great place to work,” she said. “It is not always perfect, but just have patience and work through any rough times,” she advised. “It will be worth it.”

By Amy Beth Miller

by Logan Judy

Animal behavior captivated Gordon Burghardt as a boy, and over more than half a century at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, his interdisciplinary research advanced ethology in areas including animal play, social behavior, communication, reptile behavior, enrichment, and animal cognitive abilities.

The Animal Behavior Society (ABS) recognized his outstanding lifetime achievement by awarding Burghardt the 2024 Distinguished Animal Behaviorist Award during its annual meeting in late June.

During his childhood in Wisconsin, Burghardt collected snakes. He also developed an interest in chemistry, and that was his major when he entered the University of Chicago in 1959. Despite his curiosity about animals, Burghardt said, “I was always told you couldn’t make a career, support a family, studying biology at that time.”

A class on animal behavior with Eckhard Hess led Burghardt to major in biopsychology, earning his PhD in 1966. He was drawn to UT by the head of the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, William S. Verplanck, who had worked with B.F. Skinner and other leading psychologists.

“The faculty were bright and young and growing, and they had a lot of people in experimental psychology working with animals,” Burghardt said. “I came, and I’ve been able to develop my own programs and courses, and had many grad students doing research.”

He founded a UT interdisciplinary Life Sciences Graduate Program in Ethology in 1981, one of several designed to break down departmental silos.

Although Burghardt started as an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology in 1968, he was always involved with the Department of Zoology and its graduate students. He noted the interdepartmental cooperation and collegial, supportive relationships within and between departments. “That’s developed even more now,” he said, pointing to the number of joint appointments. “I was the first one,” he said, also becoming a professor in the Department of Zoology in 1995 (now the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, or EEB).

Burghardt has worked with chemists, too, to research snakes’ chemical senses. He became one of the first editorial board members of The Journal of Chemical Ecology, one of numerous publications on which he has worked. He has served in leadership positions with multiple professional organizations too, including ABS and the American Psychological Association.

Burghardt’s excitement is evident when he talks about the first time he observed neonate snakes responding to prey chemicals, and he’s still publishing research on snake chemoreception.

Shortly after Burghardt arrived at UT, the university forged a relationship with the Great Smoky Mountains National Park for research on black bears, which were experiencing troubling encounters with tourists.

In 1970, two cubs found in the Smokies without their mother spent about seven weeks at Burghardt’s Knoxville home, until an area was ready for them in the park. The experience gave him an unusual observation opportunity.

“They were super playful,” Burghardt said. “They were the most playful animals that I’ve ever seen.”

That opened a new area for research, and Burghardt not only developed a definition of play but with his colleagues was the first to definitively document play in fish, turtles, and other species.

In 2005, his book The Genesis of Animal Play: Testing the Limits (MIT Press) examined the origins and evolution of play, reviewing evidence from species ranging from human babies to lizards, sharks, octopus, and insects. He has contributed to several other books on the topic, and his research also is extensively cited in the 2024 book Kingdom of Play: What Ball-bouncing Octopuses, Belly-flopping Monkeys, and Mud-sliding Elephants Reveal about Life Itself, by David Toomey.

Burghardt’s fascination with snakes led to numerous studies, with subjects ranging from neonates to a two-headed rat snake named IM that lived for decades in his lab.

He also taught a course on the psychology of religion, when it was a joint course with the Department of Religious Studies. “Snakes are the most important animal in religions,” he said, pointing around his office in the Austin Peay Memorial Building to artifacts and books from several faiths.

A trip to Panama to look at snakes led to his research on social behavior of newly hatched iguanas, uncovering social complexity unheard of in reptiles. Burghardt was unable to attend the ABS ceremony in Ontario to receive his award because it conflicted with his attending a centennial symposium at Barro Colorado Island, part of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, where he and his students observed the iguanas.

He and then-student Brian Bock served as scientific advisors on a British Broadcasting Corp. episode of Wildlife on One, “Iguanas, Living Like Dinosaurs,” narrated by David Attenborough.

Burghardt and his colleagues also studied a Komodo dragon named Kraken at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and later a Komodo dragon at Zoo Knoxville, also featured in two documentary films on play.

He is co-author of the 2021 book The Secret Social Lives of Reptiles and editor on the second edition of Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles.

“It was really important that the university supported and appreciated the kind of stuff that I was doing, even though it was not at all traditional in terms of what psychologists typically do,” he said. “My work, I think, has been pretty well recognized, as this award shows, so I was on to something.”

While Burghardt still serves on a couple committees of graduate students completing their dissertations, he notes that some of his former students are retiring.

“I just retired two years ago, but they’re not hanging on until 80, like I did,” he said. “Doing my research, what I wanted to do, keeps you younger.”

“I really love the field of animal behavior and feel that I’m still able to make substantial contributions,” said Burghardt, who in addition to publishing his own research is founding editor of a new journal, Frontiers in Ethology.

By Amy Beth Miller

by Logan Judy

Across the world, fans will soon be tuning in at all hours of the day and night to watch the Paris Olympics. In a world where on-demand media streaming is now increasingly the norm, sport is something of a rarity. It’s watched live, often with other people. The joy, or heartbreak, is shared.

Can something as simple as watching a sporting competition at the same time bring people closer together? In this episode of The Conversation Weekly podcast, we explore this question with a psychologist who studies the impact of shared experiences.

In his experimental psychology lab at the University of Tennessee, Garriy Shteynberg creates situations in which his test subjects go through an experience together. “We’re trying to amp up this feeling of shared experience or shared attention,” he explains. It could be watching a video together, something sad, or funny. Or asking people to work towards a goal, such as memorising a list of words.

The results suggest that, when compared to control conditions in which someone experiences something alone or at a slightly different time to others, the shared attention of experiencing something together amplifies the experience and can even give people more motivation to complete a task.

We found that if I give you a surprise test after the fact, if you co-experience the list of words, you’re better able to recall that list versus if you experience them alone. If we co-experience an emotional scene, we find that people feel more emotional … so if it’s a happy scene, people feel happier … if it’s a sad scene … people feel sadder. It amplifies whatever that stimulus is.

Shteynberg’s experiments led him to develop what he calls the theory of the collective mind.

The idea is that our individual minds not only track where we diverge, but they also track where we converge with others. When you create a collective mind, it’s as if the perspective broadens, it becomes a “we perspective”.

His own experience of immigrating to the US from the Soviet Union as a child influences Shteynberg’s thinking about collective perspectives.

In the Soviet Union, collective consciousness was emphasised all the time. In the United States, it’s quite the opposite. Most of the time, collective consciousness is something to be afraid of. It is something that put in the background. You want individual consciousness, individual reasoning. Both of those outlooks are mistaken in a way.

He argues that people have individual thoughts and experiences, and simultaneously, they also have collective ones. Both of those matter to how they experiences the world.

Shteynberg is now interested in whether shared experiences can also help bring people together, particularly in the context of increasing political polarisation.

Shared experiences form this minimal social connection that doesn’t require us to share identities, ideologies or even beliefs … The idea that we are in the same room together, that we might be watching the same news is an important social bridge upon which things can be built.

Shteynberg says that in many different ways, irrespective of their politics, people believe they share a basic experience with others, whether that’s how they live, work, or even watching something like the Olympics on TV.

I think the focus being on the deep division and that always being front and centre of our shared experience obscures the fact that we are in fact of collective mind to a great number of things.

To listen to the full interview with Garriy Shteynberg about his research, subscribe to The Conversation Weekly podcast, which also features Maggie Villiger, senior science editor at The Conversation in the US. You can also read an article Shteynberg wrote about his research on the collective mind.

We’re running a listener survey to hear what you think about The Conversation Weekly podcast. It should take just a few minutes of your time and we’d really appreciate your thoughts. Please consider filling it in.

A transcript of this episode is available on Apple Podcasts.

Newsclips in this episode from BBC Sport.

This episode of The Conversation Weekly was written and produced by Katie Flood with assistance from Mend Mariwany. Sound design was by Eloise Stevens, and our theme music is by Neeta Sarl.

You can find us on Instagram at theconversationdotcom or via email. You can also subscribe to The Conversation’s free daily email here.

Listen to The Conversation Weekly via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed or find out how else to listen here.![]()

Gemma Ware, Host, The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

by Logan Judy

by Randall Brown

Rachel Laribee came to UT Knoxville from Arlington, Tennessee, near Memphis, and will graduate this spring with not just a double major in psychology and women, gender, and sexuality studies, but also a double minor in neuroscience and sociology.

Laribee participated in a project of great cultural significance during her studies, working on the Social Action Research Team with Professor Patrick Grzanka, divisional dean for social sciences within the College of Arts and Sciences.

“Rachel has been an indispensable part of the Social Action Research Team this year,” said Grzanka. “Her commitment to producing rigorous scholarly research on pressing social issues is unparalleled. All the graduate students on the team and my faculty co-investigator came to value Rachel’s precision, attention to detail, and keen analytic insight over the past two years. Her future as a clinician and advocate for youth is the brightest.”

Team members investigated undergraduate emerging adults’ attitudes towards abortion and reproductive rights following the Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade.

“Not only was it a topic that I was deeply interested and passionate about, but it also enabled me to be directly involved in a study from the ground up,” said Laribee. “It made me significantly more confident as a researcher.”

The next stage in Laribee’s career will be working toward her master’s degree in child studies, on a clinical and developmental research track, at Vanderbilt’s Peabody College. Then, onward to a PhD program.

She encourages future Vols to embrace projects that take them beyond the classroom.

“I would say that the best thing you can do for your education is engage in diverse research projects,” said Laribee. “I’ve worked with faculty in the College of Nursing, the College of Education, and the College of Arts and Sciences, and all these projects have been incredibly fulfilling and allowed me to learn new things about myself and my interests for a future career. Be brave about reaching out too!”

The College of Arts and Sciences congratulates Rachel Laribee for successfully navigating her interdisciplinary blend of majors and minors and exemplifying the Volunteer Spirit.