Burghardt Paper Earns Biosemiotics Award

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy

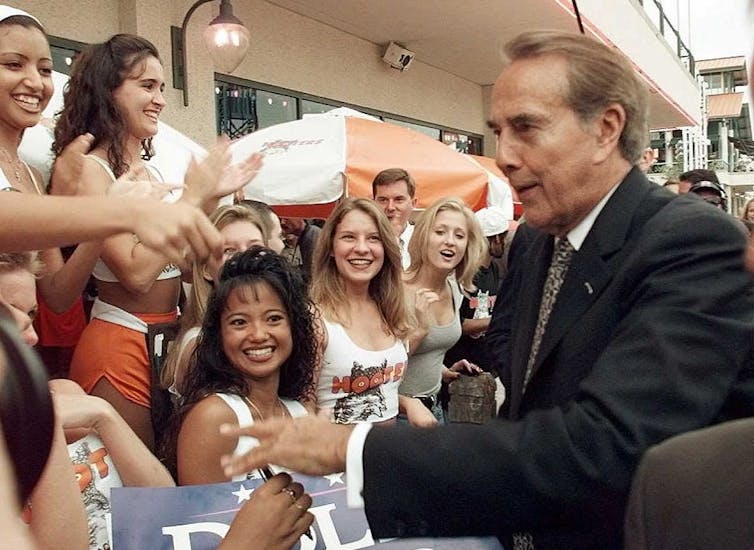

In 1983, six businessmen got together and opened the first Hooters restaurant in Clearwater, Florida. Hooters of America LLC quickly became a restaurant chain success story.

With its scantily clad servers and signature breaded wings, the chain sells sex appeal in addition to food – or as one of the company’s mottos puts it: “You can sell the sizzle, but you have to deliver the steak.” It inspired a niche restaurant genre called “breastaurants,” with eateries such as the Tilted Kilt Pub & Eatery and Twin Peaks replicating Hooters’ busty business model.

A decade ago, business was booming for breastaurant chains, with these companies experiencing record sales growth.

Today it’s a different story. Declining sales, rising costs and a large debt burden of approximately US$300 million have threatened Hooters’ long-term outlook. In summer 2024, the chain closed over 40 of its restaurants across the U.S. In February 2025, Bloomberg reported that the company was on the verge of filing for bankruptcy.

Hooters isn’t necessarily going away for good. But it’s certainly looking like there will be fewer opportunities for women to work as “Hooters Girls” – and for customers to ogle at them.

As a psychologist, I was originally interested in studying servers at breastaurants because I could sense an interesting dynamic at play. On the one hand, it can feel good to be complimented for your looks. On the other hand, I also wondered whether constantly being critiqued might eventually wear these servers down.

So my research team and I decided to study what it was like to work in places like Hooters.

In a series of studies, here’s what we found.

More so than most restaurants, managers at breastaurants like Hooters seek to strictly regulate how their employees look and act.

For one of our studies, we interviewed 11 women who worked in breastaurants.

Several of them said that they were told to be “camera ready” at all times.

One described being given a booklet with exacting standards outlining her expected appearance, down to “nails, hair, makeup, brushing your teeth, wearing deodorant.” She had to promise to stay the same weight and height, wear makeup every shift and not change her hairstyle.

Beyond a carefully constructed physical appearance, the servers relayed that they were also expected to be confident, cheerful, charming, outgoing and emotionally steeled. They were instructed to make male customers feel special, to be their “personal cheerleaders,” as one interviewee put it, and to never challenge them.

Suffice it say, these demands can be unrealistic – and many of the servers we interviewed described becoming emotionally drained and eventually souring on the role.

It probably won’t come as a surprise that Hooters servers often encounter lewd remarks, sexual advances and other forms of sexual harassment from customers.

But because their managers often tolerate this behavior from customers, it created the added burden of what psychologists call “double-binds” – situations where contradictory messages make it impossible to respond properly.

For example, say a regular customer who’s a generous tipper decides to proposition a server. Now she’s in a predicament. She’s been instructed to make customers feel special. And he’s already left a big tip, in addition to being a regular. But she also feels creeped out, and his advances make her feel worthless. Should she push back?

You might assume that managers, aware that their scantily clad employees would be more likely to face harassment, would try to set boundaries and throw out customers who treated servers poorly. But we found that waitresses at breastaurants have less support from both management and their co-workers than servers at other restaurants.

“Unfortunately, the girls are a dime a dozen, and that’s how they’re treated,” a former server and corporate trainer at a breastaurant explained.

The lack of co-worker support might also come as a surprise. Rather than standing in solidarity, the servers tended to compete for favoritism, better shifts and raises from their bosses. Gossiping, name-calling and scapegoating were commonplace.

My research team also wanted to learn more about the specific emotional and psychological costs of working in these types of environments.

Psychologists Barbara Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Robert have found that mental health problems that disproportionately affect women often coincide with sexual objectification.

So we weren’t surprised to find that servers working in sexually objectifying restaurant environments, such as Hooters and Twin Peaks, reported more symptoms of depression, anxiety and disordered eating than those working in other restaurants. In addition, they wanted to be thinner, were more likely to monitor their weight and appearance, and were more dissatisfied with their bodies. Hooters didn’t reply to a request for comment on this story.

Given our findings, you might wonder why any women would choose to work in places like Hooters in the first place.

The women we interviewed said that they sought work in breastaurants to make more money and have more flexibility.

A number of servers in one of our studies noted that they could make more money this way than waitressing at a regular restaurant or in other “real” jobs.

For example, one of the servers we interviewed used to work at a more run-of-the-mill restaurant.

“It was OK, I made OK money,” she told us. “But working at Hooters … I’ve walked out with hundreds of dollars in one shift.”

All the women we interviewed were in college or were mothers. So they enjoyed the high degree of flexibility in their work schedule that breastaurants provided.

Finally, several of them had previously experienced objectification while growing up, or they’d participated in activities centered on physical appearance, such as beauty pageants and cheerleading. This likely contributed to their decision to work at a Hooters or one of its competitors: They’d been objectified as adolescents, and so they found themselves drawn to these kinds of setting as adults.

Even so, our research suggests that the financial rewards and flexibility of working in breastaurants probably aren’t worth the potential psychological costs.![]()

Dawn Szymanski, Professor of Psychology, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy

by Logan Judy

Animal behavior captivated Gordon Burghardt as a boy, and over more than half a century at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, his interdisciplinary research advanced ethology in areas including animal play, social behavior, communication, reptile behavior, enrichment, and animal cognitive abilities.

The Animal Behavior Society (ABS) recognized his outstanding lifetime achievement by awarding Burghardt the 2024 Distinguished Animal Behaviorist Award during its annual meeting in late June.

During his childhood in Wisconsin, Burghardt collected snakes. He also developed an interest in chemistry, and that was his major when he entered the University of Chicago in 1959. Despite his curiosity about animals, Burghardt said, “I was always told you couldn’t make a career, support a family, studying biology at that time.”

A class on animal behavior with Eckhard Hess led Burghardt to major in biopsychology, earning his PhD in 1966. He was drawn to UT by the head of the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, William S. Verplanck, who had worked with B.F. Skinner and other leading psychologists.

“The faculty were bright and young and growing, and they had a lot of people in experimental psychology working with animals,” Burghardt said. “I came, and I’ve been able to develop my own programs and courses, and had many grad students doing research.”

He founded a UT interdisciplinary Life Sciences Graduate Program in Ethology in 1981, one of several designed to break down departmental silos.

Although Burghardt started as an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology in 1968, he was always involved with the Department of Zoology and its graduate students. He noted the interdepartmental cooperation and collegial, supportive relationships within and between departments. “That’s developed even more now,” he said, pointing to the number of joint appointments. “I was the first one,” he said, also becoming a professor in the Department of Zoology in 1995 (now the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, or EEB).

Burghardt has worked with chemists, too, to research snakes’ chemical senses. He became one of the first editorial board members of The Journal of Chemical Ecology, one of numerous publications on which he has worked. He has served in leadership positions with multiple professional organizations too, including ABS and the American Psychological Association.

Burghardt’s excitement is evident when he talks about the first time he observed neonate snakes responding to prey chemicals, and he’s still publishing research on snake chemoreception.

Shortly after Burghardt arrived at UT, the university forged a relationship with the Great Smoky Mountains National Park for research on black bears, which were experiencing troubling encounters with tourists.

In 1970, two cubs found in the Smokies without their mother spent about seven weeks at Burghardt’s Knoxville home, until an area was ready for them in the park. The experience gave him an unusual observation opportunity.

“They were super playful,” Burghardt said. “They were the most playful animals that I’ve ever seen.”

That opened a new area for research, and Burghardt not only developed a definition of play but with his colleagues was the first to definitively document play in fish, turtles, and other species.

In 2005, his book The Genesis of Animal Play: Testing the Limits (MIT Press) examined the origins and evolution of play, reviewing evidence from species ranging from human babies to lizards, sharks, octopus, and insects. He has contributed to several other books on the topic, and his research also is extensively cited in the 2024 book Kingdom of Play: What Ball-bouncing Octopuses, Belly-flopping Monkeys, and Mud-sliding Elephants Reveal about Life Itself, by David Toomey.

Burghardt’s fascination with snakes led to numerous studies, with subjects ranging from neonates to a two-headed rat snake named IM that lived for decades in his lab.

He also taught a course on the psychology of religion, when it was a joint course with the Department of Religious Studies. “Snakes are the most important animal in religions,” he said, pointing around his office in the Austin Peay Memorial Building to artifacts and books from several faiths.

A trip to Panama to look at snakes led to his research on social behavior of newly hatched iguanas, uncovering social complexity unheard of in reptiles. Burghardt was unable to attend the ABS ceremony in Ontario to receive his award because it conflicted with his attending a centennial symposium at Barro Colorado Island, part of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, where he and his students observed the iguanas.

He and then-student Brian Bock served as scientific advisors on a British Broadcasting Corp. episode of Wildlife on One, “Iguanas, Living Like Dinosaurs,” narrated by David Attenborough.

Burghardt and his colleagues also studied a Komodo dragon named Kraken at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and later a Komodo dragon at Zoo Knoxville, also featured in two documentary films on play.

He is co-author of the 2021 book The Secret Social Lives of Reptiles and editor on the second edition of Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles.

“It was really important that the university supported and appreciated the kind of stuff that I was doing, even though it was not at all traditional in terms of what psychologists typically do,” he said. “My work, I think, has been pretty well recognized, as this award shows, so I was on to something.”

While Burghardt still serves on a couple committees of graduate students completing their dissertations, he notes that some of his former students are retiring.

“I just retired two years ago, but they’re not hanging on until 80, like I did,” he said. “Doing my research, what I wanted to do, keeps you younger.”

“I really love the field of animal behavior and feel that I’m still able to make substantial contributions,” said Burghardt, who in addition to publishing his own research is founding editor of a new journal, Frontiers in Ethology.

By Amy Beth Miller

by Logan Judy

Across the world, fans will soon be tuning in at all hours of the day and night to watch the Paris Olympics. In a world where on-demand media streaming is now increasingly the norm, sport is something of a rarity. It’s watched live, often with other people. The joy, or heartbreak, is shared.

Can something as simple as watching a sporting competition at the same time bring people closer together? In this episode of The Conversation Weekly podcast, we explore this question with a psychologist who studies the impact of shared experiences.

In his experimental psychology lab at the University of Tennessee, Garriy Shteynberg creates situations in which his test subjects go through an experience together. “We’re trying to amp up this feeling of shared experience or shared attention,” he explains. It could be watching a video together, something sad, or funny. Or asking people to work towards a goal, such as memorising a list of words.

The results suggest that, when compared to control conditions in which someone experiences something alone or at a slightly different time to others, the shared attention of experiencing something together amplifies the experience and can even give people more motivation to complete a task.

We found that if I give you a surprise test after the fact, if you co-experience the list of words, you’re better able to recall that list versus if you experience them alone. If we co-experience an emotional scene, we find that people feel more emotional … so if it’s a happy scene, people feel happier … if it’s a sad scene … people feel sadder. It amplifies whatever that stimulus is.

Shteynberg’s experiments led him to develop what he calls the theory of the collective mind.

The idea is that our individual minds not only track where we diverge, but they also track where we converge with others. When you create a collective mind, it’s as if the perspective broadens, it becomes a “we perspective”.

His own experience of immigrating to the US from the Soviet Union as a child influences Shteynberg’s thinking about collective perspectives.

In the Soviet Union, collective consciousness was emphasised all the time. In the United States, it’s quite the opposite. Most of the time, collective consciousness is something to be afraid of. It is something that put in the background. You want individual consciousness, individual reasoning. Both of those outlooks are mistaken in a way.

He argues that people have individual thoughts and experiences, and simultaneously, they also have collective ones. Both of those matter to how they experiences the world.

Shteynberg is now interested in whether shared experiences can also help bring people together, particularly in the context of increasing political polarisation.

Shared experiences form this minimal social connection that doesn’t require us to share identities, ideologies or even beliefs … The idea that we are in the same room together, that we might be watching the same news is an important social bridge upon which things can be built.

Shteynberg says that in many different ways, irrespective of their politics, people believe they share a basic experience with others, whether that’s how they live, work, or even watching something like the Olympics on TV.

I think the focus being on the deep division and that always being front and centre of our shared experience obscures the fact that we are in fact of collective mind to a great number of things.

To listen to the full interview with Garriy Shteynberg about his research, subscribe to The Conversation Weekly podcast, which also features Maggie Villiger, senior science editor at The Conversation in the US. You can also read an article Shteynberg wrote about his research on the collective mind.

We’re running a listener survey to hear what you think about The Conversation Weekly podcast. It should take just a few minutes of your time and we’d really appreciate your thoughts. Please consider filling it in.

A transcript of this episode is available on Apple Podcasts.

Newsclips in this episode from BBC Sport.

This episode of The Conversation Weekly was written and produced by Katie Flood with assistance from Mend Mariwany. Sound design was by Eloise Stevens, and our theme music is by Neeta Sarl.

You can find us on Instagram at theconversationdotcom or via email. You can also subscribe to The Conversation’s free daily email here.

Listen to The Conversation Weekly via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed or find out how else to listen here.![]()

Gemma Ware, Host, The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

by Logan Judy

Todd M. Freeberg, University of Tennessee

Animal behavior research relies on careful observation of animals. Researchers might spend months in a jungle habitat watching tropical birds mate and raise their young. They might track the rates of physical contact in cattle herds of different densities. Or they could record the sounds whales make as they migrate through the ocean.

Animal behavior research can provide fundamental insights into the natural processes that affect ecosystems around the globe, as well as into our own human minds and behavior.

I study animal behavior – and also the research reported by scientists in my field. One of the challenges of this kind of science is making sure our own assumptions don’t influence what we think we see in animal subjects. Like all people, how scientists see the world is shaped by biases and expectations, which can affect how data is recorded and reported. For instance, scientists who live in a society with strict gender roles for women and men might interpret things they see animals doing as reflecting those same divisions.

The scientific process corrects for such mistakes over time, but scientists have quicker methods at their disposal to minimize potential observer bias. Animal behavior scientists haven’t always used these methods – but that’s changing. A new study confirms that, over the past decade, studies increasingly adhere to the rigorous best practices that can minimize potential biases in animal behavior research.

A German horse named Clever Hans is widely known in the history of animal behavior as a classic example of unconscious bias leading to a false result.

Around the turn of the 20th century, Clever Hans was purported to be able to do math. For example, in response to his owner’s prompt “3 + 5,” Clever Hans would tap his hoof eight times. His owner would then reward him with his favorite vegetables. Initial observers reported that the horse’s abilities were legitimate and that his owner was not being deceptive.

However, careful analysis by a young scientist named Oskar Pfungst revealed that if the horse could not see his owner, he couldn’t answer correctly. So while Clever Hans was not good at math, he was incredibly good at observing his owner’s subtle and unconscious cues that gave the math answers away.

In the 1960s, researchers asked human study participants to code the learning ability of rats. Participants were told their rats had been artificially selected over many generations to be either “bright” or “dull” learners. Over several weeks, the participants ran their rats through eight different learning experiments.

In seven out of the eight experiments, the human participants ranked the “bright” rats as being better learners than the “dull” rats when, in reality, the researchers had randomly picked rats from their breeding colony. Bias led the human participants to see what they thought they should see.

Given the clear potential for human biases to skew scientific results, textbooks on animal behavior research methods from the 1980s onward have implored researchers to verify their work using at least one of two commonsense methods.

One is making sure the researcher observing the behavior does not know if the subject comes from one study group or the other. For example, a researcher would measure a cricket’s behavior without knowing if it came from the experimental or control group.

The other best practice is utilizing a second researcher, who has fresh eyes and no knowledge of the data, to observe the behavior and code the data. For example, while analyzing a video file, I count chickadees taking seeds from a feeder 15 times. Later, a second independent observer counts the same number.

Yet these methods to minimize possible biases are often not employed by researchers in animal behavior, perhaps because these best practices take more time and effort.

In 2012, my colleagues and I reviewed nearly 1,000 articles published in five leading animal behavior journals between 1970 and 2010 to see how many reported these methods to minimize potential bias. Less than 10% did so. By contrast, the journal Infancy, which focuses on human infant behavior, was far more rigorous: Over 80% of its articles reported using methods to avoid bias.

It’s a problem not just confined to my field. A 2015 review of published articles in the life sciences found that blind protocols are uncommon. It also found that studies using blind methods detected smaller differences between the key groups being observed compared to studies that didn’t use blind methods, suggesting potential biases led to more notable results.

In the years after we published our article, it was cited regularly and we wondered if there had been any improvement in the field. So, we recently reviewed 40 articles from each of the same five journals for the year 2020.

We found the rate of papers that reported controlling for bias improved in all five journals, from under 10% in our 2012 article to just over 50% in our new review. These rates of reporting still lag behind the journal Infancy, however, which was 95% in 2020.

All in all, things are looking up, but the animal behavior field can still do better. Practically, with increasingly more portable and affordable audio and video recording technology, it’s getting easier to carry out methods that minimize potential biases. The more the field of animal behavior sticks with these best practices, the stronger the foundation of knowledge and public trust in this science will become.

Todd M. Freeberg, Professor and Associate Head of Psychology, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

by Logan Judy

During the 2023 College of Arts and Sciences Faculty Convocation, several faculty in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience were honored for excellence in teaching, advising, research, and outreach.

Schulz is a remarkable scholar and educator whose actions on campus, regionally, and nationally, demonstrate an unwavering commitment to increasing academic representation of and support for scholars from historically marginalized groups.

Schulz’s diversity leadership is perhaps best exemplified by her developing and launching a pilot, cross-institutional research training program between the psychology departments at UT Knoxville and the historically Black university Tennessee State University called STARS (Scholarly Trainees Acquiring Research Skills). The program was designed to prepare TSU students for graduate-level research in psychology and support their transition into graduate school.

Schulz energized department-wide involvement of faculty and graduate students as research mentors, academic coaches, and peer mentors. TSU students from the first cohort are now thriving in graduate school.

Tas is an outstanding teacher and mentor who cares deeply about her students’ learning. She has taught courses at the undergraduate and graduate level, largely focused on research methods, which are some of the most difficult courses for psychology majors.

Tas demonstrates remarkable skill in engaging students and providing opportunities to apply the material learned in her courses. She encourages students to ask questions and actively participate in discussions. Students in her courses describe her as “an amazing professor,” “always accessible,” and “incredibly knowledgeable.” In addition to the courses she teaches, Tas is an extremely sought-after mentor at the undergraduate and graduate levels. Her incredible passion about teaching and mentoring truly energizes her students.

Schulz exemplifies our college’s commitment to outstanding advising, implementing proactive and developmental advising models to build positive working relationships with students in support of their academic and career goals. Schulz is committed to supporting all students, and especially under-represented minority students. Students consistently express gratitude for her care and concern for their personal well-being in course evaluations.

One student noted, “Schulz thinks of the students who tend to be shy and embarrassed to ask questions in class and the students who may not be doing well and openly offers her most undivided attention and support to assure us that she will always be there to help. Schulz is more than a professor, teacher, instructor—she is a life mentor and an inspiration.”

Elledge’s research program is focused on bullied, socially marginalized, and anxious youth in the Knoxville community. He is a highly valued and accomplished associate professor and associate director of clinical training for the clinical psychology PhD program in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience. Elledge has particular interest in developing school-based interventions that can promote or enrich the peer relationships of at-risk youth.

His commitment to serving children and families in the Knoxville community is exceptionally impressive. His Recess VOLs program pairs at-risk children with UT student mentors who visit children twice weekly for two academic semesters. The program has placed approximately 450 UT students with children across 10 Knox County elementary schools, serving approximately 300 youth.

Deborah Welsh has been a faculty member in psychology at UT for more than 30 years and has an exceptional record of research scholarship and student research mentorship. Her research program has focused on understanding adolescent and emerging adults’ romantic relationships and their impact on functioning and has been funded by multi-year research grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Even while serving for 10 years as head of the psychology department, Welsh remained research active. She is passionate about research mentoring of undergraduate and graduate students. Her mentees have had successful careers and received elite postdoctoral fellowships and national awards. In recognition of her research accomplishments, Welsh has received numerous awards from UT Knoxville, including most recently a Chancellor’s Professorship, the 2023 College of Arts and Sciences College Marshal, and the 2023 Extraordinary Service to the University Award.

by Logan Judy

Sarah Lamer’s research into the psychology of social biases found favor with an international audience this year, earning her a spot on the Association for Psychological Science (APS) roster of Rising Stars for 2024.

The APS is the leading international organization dedicated to advancing scientific psychology across disciplinary and geographic borders. Lamer, assistant professor in the UT Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, is proud to be recognized among the top early-career colleagues in her field.

“This acknowledges the importance and rigor of my scientific work as well as the intensive mentorship model I take in my lab,” said Lamer. She works alongside her graduate students Darla Bonagura and Gillian Preston in her Social Perception and Cognition (SPĀC) lab.

“I work closely with my skilled team of graduate and undergraduate mentees to explore important and timely questions about why bias exists, where it originates, and why it is so fluently perpetuated,” she said. “This accolade recognizes the important work that we do as we discover answers to these critical questions.”

One of her research projects, “The Angry Crowd Bias: Social, Cognitive, and Perceptual Mechanisms,” is supported by a National Science Foundation grant that enables her to design, analyze, and conduct studies; mentor graduate students through the research process; share their work at professional conferences; and conduct workshops to share a love of science with students in the local Knoxville community.

The angry crowd bias is a psychological phenomenon people can experience when first exposed to faces that are hard to see or that have subtle expressions—notably among a “many faces in a crowd” situation. People can report that these faces look threatening, even when they are not.

“We know from a bulk of research that people are able to detect average information about a crowd with some accuracy,” said Lamer. “But perception is more complex than that. Accuracy and bias always work together in human perception.”

Lamer and her team hypothesized that this complex mix causes a tendency to perceive an unfamiliar crowd’s mood to be potentially dangerous.

“We focused on anger bias since crowds can pose a stronger threat to safety than an individual,” she said. “If a crowd is angry at you, you are at much higher risk than if an individual is angry at you. In other words, it is functional to be wary of a crowd.”

The team uses state-of-the-art methods and statistical tools to examine a viewer’s visual attention to faces—eye-tracking data, signal-detection methods, and drift-diffusion modeling—to track what people focus on while making emotional judgments. Then they assess what is accurate and what leads to bias.

“The approach makes it possible to track visual patterns—for example, which faces people look at first in a crowd, how long they look at each face, and whether they ignore anyone,” said Lamer. “All of which are likely to be affected by the race and gender of the faces themselves.”

This work is timely in relation to widespread protests in the US over the past several years and the divergent interpretations these crowds have received across public perception—potentially due in part to the racial and gender makeup of these assemblies.

“With this social backdrop in mind—and understanding that, according to event-forecasting models, social unrest is likely to increase in the future—this research was designed to identify the people whom negative crowd biases are most likely to affect, where these biased judgments come from, and how malleable they might be,” said Lamer. “We plan to complete data analysis on our current study by the end of the semester.”